MENU

(April 15, 2016 - stories by Ralph Kurtenbach) Germs with elaborate names such as Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus are featured prominently in a new book detailing the findings of 15 years of research done at a mission hospital in Ecuador.

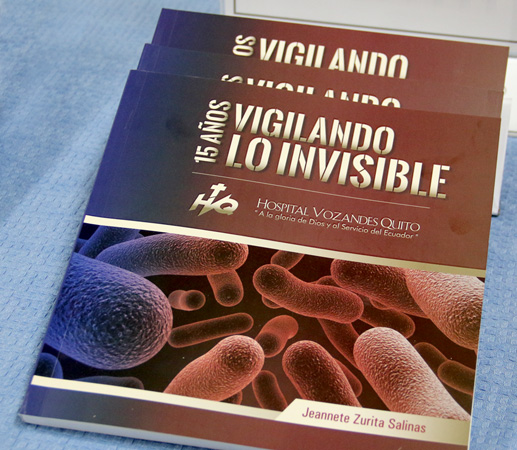

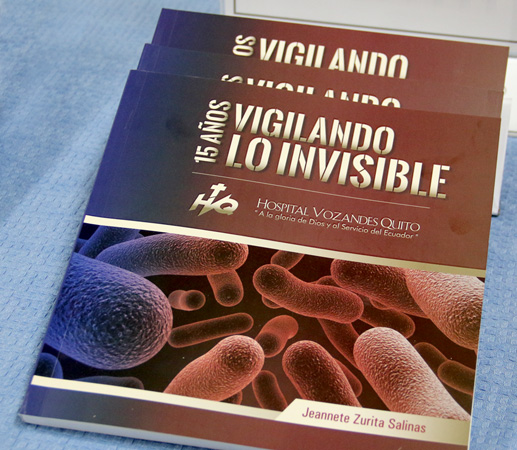

The 246-page book, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible (15 Years of Watching the Invisible), is an academic work that responds to concerns expressed by healthcare and research experts who met in Venezuela for a Pan-American Conference on Antimicrobial Resistance.

The 246-page book, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible (15 Years of Watching the Invisible), is an academic work that responds to concerns expressed by healthcare and research experts who met in Venezuela for a Pan-American Conference on Antimicrobial Resistance.

A tour de force of documented and chronicled germs, the book debuted in late 2015 when its author, Dr. Jeannete Zurita, addressed those gathered for a formal observation of the 60th anniversary of Hospital Vozandes-Quito (HVQ) where the research took place. Zurita’s work at the Reach Beyond facility, based in Ecuador’s capital city, spans more than two decades.

“We were professionals from the disciplines of microbiology, infectology and public health as well as others,” Zurita wrote of the meeting in Caraballeda, Venezuela, in the late 1990s. The conferees debated factors contributing to increasingly resistant germs—germs not only resistant to medicines but also to other attempts at control.

The experts’ discussion pointed to suspected influences that were creating superbugs such as incorrect use of pharmaceuticals and inadequate germ monitoring efforts. Then anticipating ways to help future researchers and other professionals make informed decisions, they determined that “all the countries of the Americas, including Ecuador, committed to begin surveillance on [germ] resistance.”

The conference in Venezuela took place in late 1998. By 1999 HVQ had begun monitoring bacterial resistance in 22 Ecuadorian hospitals through the Red Nacional de Vigilancia de Resistencia Bacteriana (National Network of Surveillance of Resistant Bacteria). At the mission hospital, installation of World Health Organization software called WHONET facilitated compilation and analysis of data on microbials. In 2010 the surveillance was transferred to the Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública (INSPI).

The conference in Venezuela took place in late 1998. By 1999 HVQ had begun monitoring bacterial resistance in 22 Ecuadorian hospitals through the Red Nacional de Vigilancia de Resistencia Bacteriana (National Network of Surveillance of Resistant Bacteria). At the mission hospital, installation of World Health Organization software called WHONET facilitated compilation and analysis of data on microbials. In 2010 the surveillance was transferred to the Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública (INSPI).

Much later, the Red Nacional de Vigilancia de Antimicrobianos del Ecuador (Ecuador National Network of Antimicrobial Surveillance) was established in 2014. In addition to her work at HVQ and her privately operated laboratory, Zurita was named the network’s director.

Infection and colonization by E. coli in the Quito hospital accounted for 46 percent of all bacteria isolated during the 15-year study on over 20,000 lab samples. This put E. coli as the leading bacteria documented at the Quito facility, and it has been confirmed elsewhere as causing outbreaks of illness and sometimes deaths. In the U.S., for example, health authorities linked one such outbreak to contaminated ingredients at a restaurant chain and another outbreak to food sold at a department store franchise.

The data revealed 4,680 isolates of Staphylococcus aureus (more than one each day of the study period). Placing a distant second place after E. coli, this is the bacterium commonly known as staph. Staph infections may range from a simple boil to a far more serious episode with flesh-eating infection. Another type of staph infection—called cellulitis—involves the skin.

Coincidentally, this was the malady affecting one of Zurita’s fellow speakers at the HVQ anniversary event, Reach Beyond’s Dr. Roy Ringenberg, during his visit to Ecuador. In his speech, he praised his caregivers, some of the same colleagues with whom he had worked while serving as a missionary doctor in Ecuador.

Zurita, speaking about the book at the Oct. 15 anniversary celebration in Quito, presented her findings and later offered people signed copies of 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible. The 60th anniversary event came 16 months after the hospital’s sale was announced to employees and the public—a deal that later fell through.

Zurita, speaking about the book at the Oct. 15 anniversary celebration in Quito, presented her findings and later offered people signed copies of 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible. The 60th anniversary event came 16 months after the hospital’s sale was announced to employees and the public—a deal that later fell through.

In the book, Zurita reviewed literature of increasingly resistant bacteria and acknowledged research concurrent with the HVQ data collation. She mentioned her basic belief about resistance was “‘no man, no resistance,’ but it seems that the resistance of bacteria is more surprising than we had believed.”

On the Galapagos Islands, for example, where Ecuador has set emigration quotas, antibiotic use falls behind areas of denser populations. However, scientist Maria Cristina Thaller has found resistant bacteria among iguanas, according to Zurita. (The study did not directly interface with Zurita’s but is part of the literature.)

Research by María Dominguez-Bello in 2009 found antibiotic-resistant bacteria among the Yanomami people. Their hunter-gatherer existence in remote Venezuela affords them little contact with modern medicine or a Western diet.

Zurita cited additional discoveries, including ancient bacteria found in the permafrost of northern Canada’s Beringia region in the Yukon. Another example from the Lechuguilla Cave of New Mexico demonstrated resistant bacteria even though their habitat had never been exposed to antibiotics.

Such situations pose conundrums to researchers and beg such questions as, “Is it possible to stop resistant bacteria?” Devoting one full chapter to that exact query, Zurita notes that “MRSA is endemic in many hospitals,” especially those high in specialties and in patient numbers. MRSA—Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—“is growing worldwide and Latin America is no exception,” she wrote. As clones of these bacteria begin to circulate, they exacerbate the situation.

With another dozen Ecuadorian hospitals now reporting bacteria data along with HVQ, Zurita briefly touched upon bed count and specialty numbers, and also drew attention to hygiene practices. “The only way to change this panorama is with three indispensable requirements,” she wrote. “[These are] clean hands, clean patients and a clean hospital.”

In the book’s acknowledgments, Zurita thanks HVQ Director Dr. Ximena Pacheco. She credits the title, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible, as a suggestion offered by the hospital’s medical education director, Dr. José Luis Recalde.

Missionary Medicine Helps Further Advances Against Illness

Dr. Jeannete Zurita’s book, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible, is quietly contributing to the body of medical research literature done by Christian mission agencies, including Reach Beyond.

Zurita wrote of how the careful documentation of bacteria by the laboratory at Hospital Vozandes-Quito (HVQ) has helped to facilitate informed decisions by healthcare providers striving to confront ever increasingly resistant bugs. Zurita and others began the study began in 2000.

Zurita wrote of how the careful documentation of bacteria by the laboratory at Hospital Vozandes-Quito (HVQ) has helped to facilitate informed decisions by healthcare providers striving to confront ever increasingly resistant bugs. Zurita and others began the study began in 2000.

That same year HVQ served as a sentinel site for the detection of the H1N1 virus as well as other emerging strains of influenza. By the time of a global H1N1 pandemic in 2009, flu cases had been catalogued by an Ecuadorian physician and an expatriate missionary—Drs. Wilson Chicaiza and Richard Douce.

The two men facilitated data collection by the Peru-based U.S. Navy Tropical Disease Research Laboratory. That information went to both the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta and the World Health Organization. HVQ was also positioned to help start an influenza surveillance program in Ecuador’s largest healthcare facility, Hospital Luis Vernaza, in Guayaquil.

In late 2011 Chicaiza and Douce jointly published the most extensive documentation of the viral causes of influenza-like illnesses in Ecuador. Positing that “tropical countries are thought to play an important role in the global behavior of respiratory infections such as influenza,” their article appeared in PLoS ONE, a digital trade magazine of the Public Library of Science.

In late 2011 Chicaiza and Douce jointly published the most extensive documentation of the viral causes of influenza-like illnesses in Ecuador. Positing that “tropical countries are thought to play an important role in the global behavior of respiratory infections such as influenza,” their article appeared in PLoS ONE, a digital trade magazine of the Public Library of Science.

A central question asked by the study was whether Ecuador was a source of epidemics or if the Andean country “was simply a stopping-off place as the wave of epidemic flu circulates through the world?” Douce concluded that “our data suggests the latter.”

Such contributions by missionary physicians and their national colleagues are not new, according to Ken Walker, writing in the periodical Christianity Today. “In the 1950s and 1960s, Irish doctor Dennis Burkitt identified a new type of cancer that came to be called Burkitt lymphoma while investigating jaw tumors in Ugandan children,” Walker wrote in a mid-2013 edition of the magazine.

“Jack Hough, who played a key role in the founding of global Christian health organization MAP International, was a pioneer in microscopic ear surgery,” continued Walker. “Surgeon Paul Brand earned acclaim for his innovative treatments of leprosy patients in India.”

Among the filed documents of Dr. Frank Richards, is a copy of an article on river blindness published by Dr. Ron Guderian in 1982. Richards, who now heads the Global River Blindness Elimination Program at the Atlanta-based Carter Center, noted Guderian’s assertion—in both that article and an earlier one—that river blindness was present in the Americas and not just on the African continent.

Among the filed documents of Dr. Frank Richards, is a copy of an article on river blindness published by Dr. Ron Guderian in 1982. Richards, who now heads the Global River Blindness Elimination Program at the Atlanta-based Carter Center, noted Guderian’s assertion—in both that article and an earlier one—that river blindness was present in the Americas and not just on the African continent.

“Missionary physicians have played a very important role in tropical medicine,” Richards told Seattle Pacific University’s Hannah Notess. “So I wasn’t really that surprised that a missionary physician in the boonies, seeing patients, would happen to discover a previously unknown condition.”

As a point man for river blindness research in Ecuador, Guderian co-authored dozens of scientific papers, collaborating with researchers around the world. He recalls that on one occasion upon arriving at his Quito office, he was greeted by representatives of the prestigious London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who had read his articles and wanted to work with him.

As a point man for river blindness research in Ecuador, Guderian co-authored dozens of scientific papers, collaborating with researchers around the world. He recalls that on one occasion upon arriving at his Quito office, he was greeted by representatives of the prestigious London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who had read his articles and wanted to work with him.

“In Guderian’s telling, partnerships like this seemed to happen when needed most, as answers to prayer,” wrote Notess. “The Germany-based Christian Blind Mission provided financial support. The London School provided lab facilities for research. The Catholic archdiocese of Esmeraldas provided resources to develop community health infrastructure.”

A significant boost to the work in Ecuador came with the 1987 announcement by Merck Pharmaceuticals that it would make freely available the drug ivermectin (or Mectizan®) for distribution in any country where river blindness was present, for as long as the disease persisted. This led to the World Health Organization’s official declaration in 2014 of the disease’s elimination from Ecuador.

“Together with The Carter Center and international partners,” said the center’s founder, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, “Rosalynn and I want to congratulate Ecuador for wiping out river blindness and showing that eliminating this disease from the Americas is possible.”

Community health workers had played a key role in the eradication of river blindness in Ecuador—the world’s second nation to attain that goal. Trained by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Health, they had made sure that every person in tiny river villages took an ivermectin dose semiannually. For example, in 2008 a combined 27,372 ivermectin treatments were administered to more than 16,000 people.

Faith-based groups’ involvement in healthcare provision was recognized by a mid-2015 study cited by The Lancet medical journal. “Religious groups are major players in the delivery of healthcare, particularly in hard-to-reach and rural areas that are not adequately served by government,” said Edward Mills, the study’s author and a senior epidemiologist at Global Evaluative Sciences in Canada.

During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, faith groups were key mediators, according to Mills who was cited in a news story by Magdalena Mis of the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Devastated villages needed persuasion to drop their custom of embracing the dead. The faith community also provided vital medical services and support.

As professional fulfillments go, co-authoring publishable research studies with those Ecuadorians at HVQ whom he helped to train may well top Guderian’s list. Of Ecuadorians who worked with him, 18 went on for further study in Brazil, France, Mexico, the U.K. and the U.S.

The hospital’s first medical residency came about in the 1960s in ophthalmology under Dr. Gustavo Moreno’s leadership. Guderian’s investigations in Ecuador’s remote areas outside the capital city of Quito occurred during the 1980s as HVQ medical students were able to begin pursuing a family practice residency, thanks to the efforts of Drs. Ev Bruckner, Gil Wagoner and Cal Wilson. Preparations are underway for a May celebration in Quito commemorating the special anniversary dates associated with HVQ’s various residency programs.

Douce recalls teaching residents during the 1990s on the use of library skills on the Internet. “Our residents told us [in 2015] that we were the first to have email, the first to have Internet capabilities and that they’ve been in the vanguard of medical educators because of their experience … in our residency,” he said.

“And so we were advancing things that are now commonplace, and our residents were at the peak of the wave,” Douce added. “It was just a joy to be able to do that.”

Sources: Reach Beyond, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible, Response (Seattle Pacific University’s alumni magazine), Christianity Today, CNN, Thomson Reuters Foundation (charitable arm of Thomson Reuters)

The 246-page book, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible (15 Years of Watching the Invisible), is an academic work that responds to concerns expressed by healthcare and research experts who met in Venezuela for a Pan-American Conference on Antimicrobial Resistance.

The 246-page book, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible (15 Years of Watching the Invisible), is an academic work that responds to concerns expressed by healthcare and research experts who met in Venezuela for a Pan-American Conference on Antimicrobial Resistance.A tour de force of documented and chronicled germs, the book debuted in late 2015 when its author, Dr. Jeannete Zurita, addressed those gathered for a formal observation of the 60th anniversary of Hospital Vozandes-Quito (HVQ) where the research took place. Zurita’s work at the Reach Beyond facility, based in Ecuador’s capital city, spans more than two decades.

“We were professionals from the disciplines of microbiology, infectology and public health as well as others,” Zurita wrote of the meeting in Caraballeda, Venezuela, in the late 1990s. The conferees debated factors contributing to increasingly resistant germs—germs not only resistant to medicines but also to other attempts at control.

The experts’ discussion pointed to suspected influences that were creating superbugs such as incorrect use of pharmaceuticals and inadequate germ monitoring efforts. Then anticipating ways to help future researchers and other professionals make informed decisions, they determined that “all the countries of the Americas, including Ecuador, committed to begin surveillance on [germ] resistance.”

The conference in Venezuela took place in late 1998. By 1999 HVQ had begun monitoring bacterial resistance in 22 Ecuadorian hospitals through the Red Nacional de Vigilancia de Resistencia Bacteriana (National Network of Surveillance of Resistant Bacteria). At the mission hospital, installation of World Health Organization software called WHONET facilitated compilation and analysis of data on microbials. In 2010 the surveillance was transferred to the Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública (INSPI).

The conference in Venezuela took place in late 1998. By 1999 HVQ had begun monitoring bacterial resistance in 22 Ecuadorian hospitals through the Red Nacional de Vigilancia de Resistencia Bacteriana (National Network of Surveillance of Resistant Bacteria). At the mission hospital, installation of World Health Organization software called WHONET facilitated compilation and analysis of data on microbials. In 2010 the surveillance was transferred to the Instituto Nacional de Investigación en Salud Pública (INSPI).Much later, the Red Nacional de Vigilancia de Antimicrobianos del Ecuador (Ecuador National Network of Antimicrobial Surveillance) was established in 2014. In addition to her work at HVQ and her privately operated laboratory, Zurita was named the network’s director.

Infection and colonization by E. coli in the Quito hospital accounted for 46 percent of all bacteria isolated during the 15-year study on over 20,000 lab samples. This put E. coli as the leading bacteria documented at the Quito facility, and it has been confirmed elsewhere as causing outbreaks of illness and sometimes deaths. In the U.S., for example, health authorities linked one such outbreak to contaminated ingredients at a restaurant chain and another outbreak to food sold at a department store franchise.

The data revealed 4,680 isolates of Staphylococcus aureus (more than one each day of the study period). Placing a distant second place after E. coli, this is the bacterium commonly known as staph. Staph infections may range from a simple boil to a far more serious episode with flesh-eating infection. Another type of staph infection—called cellulitis—involves the skin.

Coincidentally, this was the malady affecting one of Zurita’s fellow speakers at the HVQ anniversary event, Reach Beyond’s Dr. Roy Ringenberg, during his visit to Ecuador. In his speech, he praised his caregivers, some of the same colleagues with whom he had worked while serving as a missionary doctor in Ecuador.

Zurita, speaking about the book at the Oct. 15 anniversary celebration in Quito, presented her findings and later offered people signed copies of 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible. The 60th anniversary event came 16 months after the hospital’s sale was announced to employees and the public—a deal that later fell through.

Zurita, speaking about the book at the Oct. 15 anniversary celebration in Quito, presented her findings and later offered people signed copies of 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible. The 60th anniversary event came 16 months after the hospital’s sale was announced to employees and the public—a deal that later fell through.In the book, Zurita reviewed literature of increasingly resistant bacteria and acknowledged research concurrent with the HVQ data collation. She mentioned her basic belief about resistance was “‘no man, no resistance,’ but it seems that the resistance of bacteria is more surprising than we had believed.”

On the Galapagos Islands, for example, where Ecuador has set emigration quotas, antibiotic use falls behind areas of denser populations. However, scientist Maria Cristina Thaller has found resistant bacteria among iguanas, according to Zurita. (The study did not directly interface with Zurita’s but is part of the literature.)

Research by María Dominguez-Bello in 2009 found antibiotic-resistant bacteria among the Yanomami people. Their hunter-gatherer existence in remote Venezuela affords them little contact with modern medicine or a Western diet.

Zurita cited additional discoveries, including ancient bacteria found in the permafrost of northern Canada’s Beringia region in the Yukon. Another example from the Lechuguilla Cave of New Mexico demonstrated resistant bacteria even though their habitat had never been exposed to antibiotics.

Such situations pose conundrums to researchers and beg such questions as, “Is it possible to stop resistant bacteria?” Devoting one full chapter to that exact query, Zurita notes that “MRSA is endemic in many hospitals,” especially those high in specialties and in patient numbers. MRSA—Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus—“is growing worldwide and Latin America is no exception,” she wrote. As clones of these bacteria begin to circulate, they exacerbate the situation.

With another dozen Ecuadorian hospitals now reporting bacteria data along with HVQ, Zurita briefly touched upon bed count and specialty numbers, and also drew attention to hygiene practices. “The only way to change this panorama is with three indispensable requirements,” she wrote. “[These are] clean hands, clean patients and a clean hospital.”

In the book’s acknowledgments, Zurita thanks HVQ Director Dr. Ximena Pacheco. She credits the title, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible, as a suggestion offered by the hospital’s medical education director, Dr. José Luis Recalde.

Missionary Medicine Helps Further Advances Against Illness

Dr. Jeannete Zurita’s book, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible, is quietly contributing to the body of medical research literature done by Christian mission agencies, including Reach Beyond.

Zurita wrote of how the careful documentation of bacteria by the laboratory at Hospital Vozandes-Quito (HVQ) has helped to facilitate informed decisions by healthcare providers striving to confront ever increasingly resistant bugs. Zurita and others began the study began in 2000.

Zurita wrote of how the careful documentation of bacteria by the laboratory at Hospital Vozandes-Quito (HVQ) has helped to facilitate informed decisions by healthcare providers striving to confront ever increasingly resistant bugs. Zurita and others began the study began in 2000.That same year HVQ served as a sentinel site for the detection of the H1N1 virus as well as other emerging strains of influenza. By the time of a global H1N1 pandemic in 2009, flu cases had been catalogued by an Ecuadorian physician and an expatriate missionary—Drs. Wilson Chicaiza and Richard Douce.

The two men facilitated data collection by the Peru-based U.S. Navy Tropical Disease Research Laboratory. That information went to both the Centers for Disease Control in Atlanta and the World Health Organization. HVQ was also positioned to help start an influenza surveillance program in Ecuador’s largest healthcare facility, Hospital Luis Vernaza, in Guayaquil.

In late 2011 Chicaiza and Douce jointly published the most extensive documentation of the viral causes of influenza-like illnesses in Ecuador. Positing that “tropical countries are thought to play an important role in the global behavior of respiratory infections such as influenza,” their article appeared in PLoS ONE, a digital trade magazine of the Public Library of Science.

In late 2011 Chicaiza and Douce jointly published the most extensive documentation of the viral causes of influenza-like illnesses in Ecuador. Positing that “tropical countries are thought to play an important role in the global behavior of respiratory infections such as influenza,” their article appeared in PLoS ONE, a digital trade magazine of the Public Library of Science.A central question asked by the study was whether Ecuador was a source of epidemics or if the Andean country “was simply a stopping-off place as the wave of epidemic flu circulates through the world?” Douce concluded that “our data suggests the latter.”

Such contributions by missionary physicians and their national colleagues are not new, according to Ken Walker, writing in the periodical Christianity Today. “In the 1950s and 1960s, Irish doctor Dennis Burkitt identified a new type of cancer that came to be called Burkitt lymphoma while investigating jaw tumors in Ugandan children,” Walker wrote in a mid-2013 edition of the magazine.

“Jack Hough, who played a key role in the founding of global Christian health organization MAP International, was a pioneer in microscopic ear surgery,” continued Walker. “Surgeon Paul Brand earned acclaim for his innovative treatments of leprosy patients in India.”

Among the filed documents of Dr. Frank Richards, is a copy of an article on river blindness published by Dr. Ron Guderian in 1982. Richards, who now heads the Global River Blindness Elimination Program at the Atlanta-based Carter Center, noted Guderian’s assertion—in both that article and an earlier one—that river blindness was present in the Americas and not just on the African continent.

Among the filed documents of Dr. Frank Richards, is a copy of an article on river blindness published by Dr. Ron Guderian in 1982. Richards, who now heads the Global River Blindness Elimination Program at the Atlanta-based Carter Center, noted Guderian’s assertion—in both that article and an earlier one—that river blindness was present in the Americas and not just on the African continent.“Missionary physicians have played a very important role in tropical medicine,” Richards told Seattle Pacific University’s Hannah Notess. “So I wasn’t really that surprised that a missionary physician in the boonies, seeing patients, would happen to discover a previously unknown condition.”

As a point man for river blindness research in Ecuador, Guderian co-authored dozens of scientific papers, collaborating with researchers around the world. He recalls that on one occasion upon arriving at his Quito office, he was greeted by representatives of the prestigious London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who had read his articles and wanted to work with him.

As a point man for river blindness research in Ecuador, Guderian co-authored dozens of scientific papers, collaborating with researchers around the world. He recalls that on one occasion upon arriving at his Quito office, he was greeted by representatives of the prestigious London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who had read his articles and wanted to work with him.“In Guderian’s telling, partnerships like this seemed to happen when needed most, as answers to prayer,” wrote Notess. “The Germany-based Christian Blind Mission provided financial support. The London School provided lab facilities for research. The Catholic archdiocese of Esmeraldas provided resources to develop community health infrastructure.”

A significant boost to the work in Ecuador came with the 1987 announcement by Merck Pharmaceuticals that it would make freely available the drug ivermectin (or Mectizan®) for distribution in any country where river blindness was present, for as long as the disease persisted. This led to the World Health Organization’s official declaration in 2014 of the disease’s elimination from Ecuador.

“Together with The Carter Center and international partners,” said the center’s founder, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter, “Rosalynn and I want to congratulate Ecuador for wiping out river blindness and showing that eliminating this disease from the Americas is possible.”

Community health workers had played a key role in the eradication of river blindness in Ecuador—the world’s second nation to attain that goal. Trained by the Ecuadorian Ministry of Health, they had made sure that every person in tiny river villages took an ivermectin dose semiannually. For example, in 2008 a combined 27,372 ivermectin treatments were administered to more than 16,000 people.

Faith-based groups’ involvement in healthcare provision was recognized by a mid-2015 study cited by The Lancet medical journal. “Religious groups are major players in the delivery of healthcare, particularly in hard-to-reach and rural areas that are not adequately served by government,” said Edward Mills, the study’s author and a senior epidemiologist at Global Evaluative Sciences in Canada.

During the Ebola outbreak in West Africa, faith groups were key mediators, according to Mills who was cited in a news story by Magdalena Mis of the Thomson Reuters Foundation. Devastated villages needed persuasion to drop their custom of embracing the dead. The faith community also provided vital medical services and support.

As professional fulfillments go, co-authoring publishable research studies with those Ecuadorians at HVQ whom he helped to train may well top Guderian’s list. Of Ecuadorians who worked with him, 18 went on for further study in Brazil, France, Mexico, the U.K. and the U.S.

The hospital’s first medical residency came about in the 1960s in ophthalmology under Dr. Gustavo Moreno’s leadership. Guderian’s investigations in Ecuador’s remote areas outside the capital city of Quito occurred during the 1980s as HVQ medical students were able to begin pursuing a family practice residency, thanks to the efforts of Drs. Ev Bruckner, Gil Wagoner and Cal Wilson. Preparations are underway for a May celebration in Quito commemorating the special anniversary dates associated with HVQ’s various residency programs.

Douce recalls teaching residents during the 1990s on the use of library skills on the Internet. “Our residents told us [in 2015] that we were the first to have email, the first to have Internet capabilities and that they’ve been in the vanguard of medical educators because of their experience … in our residency,” he said.

“And so we were advancing things that are now commonplace, and our residents were at the peak of the wave,” Douce added. “It was just a joy to be able to do that.”

Sources: Reach Beyond, 15 Años Vigilando Lo Invisible, Response (Seattle Pacific University’s alumni magazine), Christianity Today, CNN, Thomson Reuters Foundation (charitable arm of Thomson Reuters)